#DIFFERENCE BETWEEN HUMAN AND CHIMPANZEE HAND SERIES#

The present series of experiments was designed to decide between these two alternatives. Thus it is unclear whether or not the neuronal mechanisms involved in the use of simple tools, such as a rake, are similar in humans and monkeys. According to this hypothesis only the use of more complex tools requires special neuronal mechanisms typical of humans ( Johnson-Frey, 2004 Frey, 2008). On the other hand, the finding that the training induces the appearance of bimodal visuo-tactile properties in parietal neurons ( Iriki et al., 1996), has led to the suggestion that the use of simple tools might rely on similar mechanisms in both species ( Maravita and Iriki, 2004). Only humans should therefore possess specialized neuronal mechanisms allowing them to understand the functional properties of tools, a species difference that should apply to all tools, both simple and complex. Is this capacity to understand tools mediated by an evolutionarily new neural substrate peculiar to humans? Since primates in general exhibit the same level of understanding of tool use, whether they use them spontaneously or only after training, it has been suggested that primates rely on domain-general rather than domain-specific knowledge ( Santos et al., 2006). The available evidence ( Visalberghi and Limongelli, 1994 Povinelli, 2000 Mulcahy and Call, 2006 Martin-Ordas et al., 2008) indicates that chimpanzees may have some causal understanding of a trap, for instance, but lack the ability to establish analogical relationships between perceptually disparate but functionally equivalent tasks ( Martin-Ordas et al., 2008 Penn et al., 2008). While it is clear that the use of tools by humans reflects an understanding of the causal relationship between the tool and the action goals ( Johnson-Frey, 2003), this is far less true for apes. Except for Cebus monkeys ( Visalberghi and Trinca, 1989 Moura and Lee, 2004), most monkeys, including macaques, vervets, tamarins, marmosets, and lemurs, use tools only after training ( Natale et al., 1988 Hauser, 1997 Santos et al., 2005, 2006 Spaulding and Hauser, 2005). However, there is now general agreement that chimpanzees also use tools, in captivity ( Kohler, 1927) as well as in the wild ( Beck, 1980 Whiten et al., 1999). Tool use has long been considered a uniquely human characteristic ( Oakley, 1956), dating back 2.5 Mi years ( Ambrose, 2001). Tools are mechanical implements that allow individuals to achieve goals that otherwise would be difficult or impossible to reach. These results shed new light on the changes of the hominid brain during evolution. In conclusion, while the observation of a grasping hand activated similar regions in humans and monkeys, an additional specific sector of IPL devoted to tool use has evolved in Homo sapiens, although tool-specific neurons might reside in the monkey grasping regions. This latter site was considered human-specific, as it was not observed in monkey IPL for any of the tool videos presented, even after monkeys had become proficient in using a rake or pliers through extensive training. In humans, the observation of actions done with simple tools yielded an additional, specific activation of a rostral sector of the left inferior parietal lobule (IPL). In both species, the observation of an action, regardless of how performed, activated occipitotemporal, intraparietal, and ventral premotor cortex, bilaterally. In a comparative fMRI study, we scanned a large cohort of human volunteers and untrained monkeys, as well as two monkeys trained to use tools, while they observed hand actions and actions performed using simple tools.

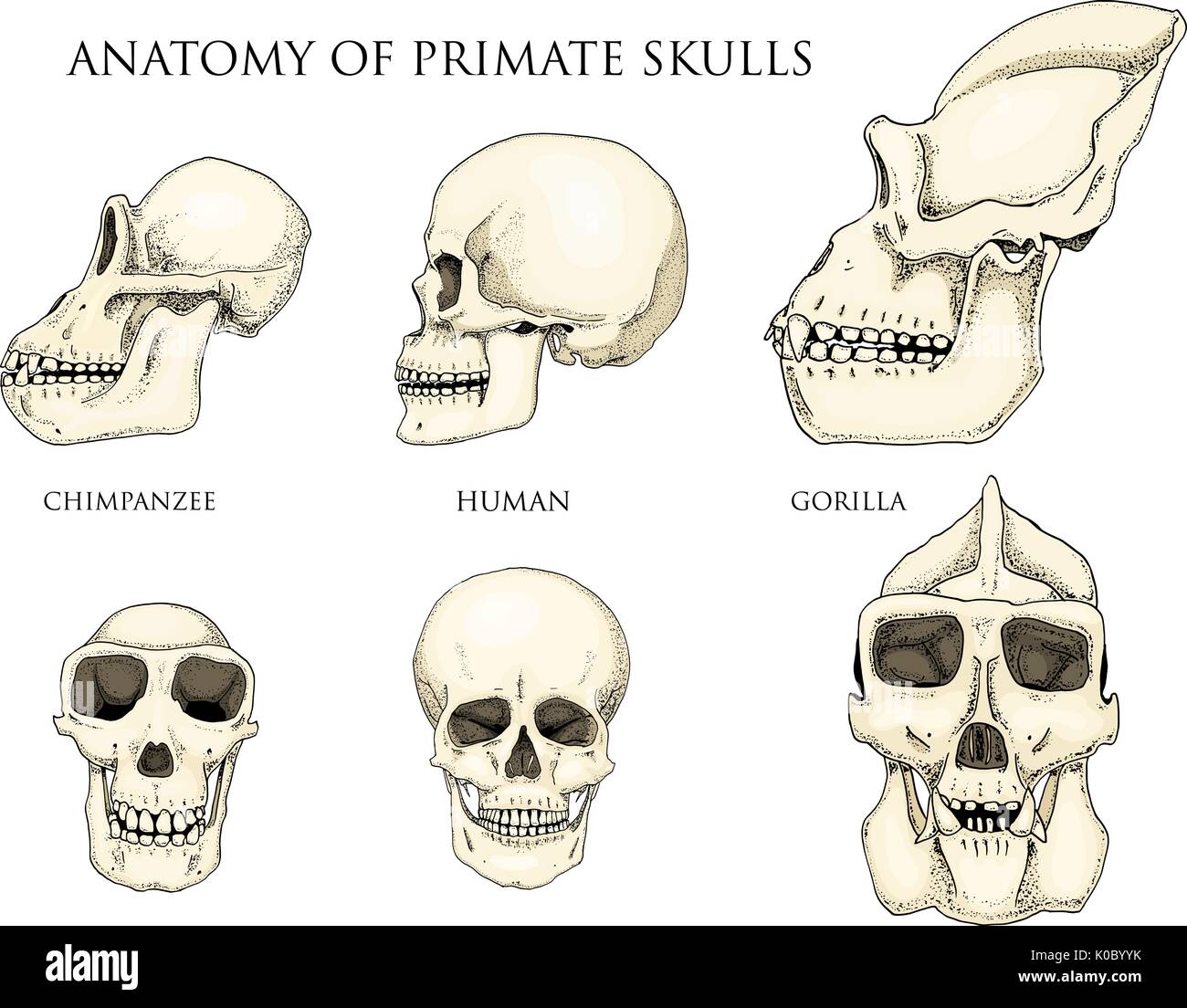

Though other species of primates also use tools, humans appear unique in their capacity to understand the causal relationship between tools and the result of their use.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)